DCMP: Essay

As part of this module, I must write a 2000 word essay on one of the questions below. This accounts to 30% of my mark for this module.

DEADLINE: 1pm, 7th May, 2024

1. Stuart Hall states that the Media ‘are the main channels of public discourse in our segregated society. They transmit stereotypes of one group to other groups.’ (Hall,1971). With reference to one specific visual form of Media, consider how the representation of a specific social or cultural group or community constructs and reinforces stereotypes.

2. Please do the following reading and answer the question below:

Rushton, R. (2013) ‘Realism, Reality and Authenticity’, in The Reality of Film: Theories of Filmic Reality, Manchester: Manchester University Press, pp. 42-78.Source:https://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/westminster/reader.action?docID=1069669

Question: Rushton argues that “one should not concentrate on cinema’s capacities for representing reality, one should begin from the position that films are, in one way or another, part of reality”. (2013: 43-44) Using specific examples, examine the idea that films and/or other media are “part of reality".

3. Please do the following reading and answer the question below:

Tsitsos, W. (2018) ‘Race, Class, and Place in the Origins of Techno and Rap Music’, in Popular Music and Society, Vol. 41(3), 270-292. Source: https://www-tandfonline-com.uow.idm.oclc.org/doi/pdf/10.1080/03007766.2018.1519098?needAccess=true

Question: According to Tsitsos, “music constitutes a ritualistic attempt to symbolically purge that which does not belong” (2018: 272). Discuss the representation of race and/or class in relation to multiple examples of contemporary popular music and/or media.

4. Please do the following reading and answer the question below:

Bartmanski, D. and Woodward, I. (2015) Vinyl: the analogue medium in the age of digital reproduction', in The Journal of Consumer Culture, Vol. 15(1), pp. 3-27.Source:https://journals-sagepub-com.uow.idm.oclc.org/doi/epub/10.1177/1469540513488403

Question: For Bartmanski and Woodward, the continued relevance of the vinyl record as an “auratic cultural icon ... sums up an important aspect of late modernity – the searchfor authenticity and meaning through the heavily mediated, digitalised andcommodified world” (2015: 19). With reference to the continued relevance of one analogue format, platform or medium, discuss the meaning of authenticity in the age of digital reproduction.

5. Please do the following reading and answer the question below:

Beckett, A. (2017) ‘Accelerationism: how a fringe philosophy predicted the future we live in’, The Guardian, Thursday 11 May 2017.3 Source: https://www.theguardian.com/world/2017/may/11/accelerationism-how-a-fringe-philosophy-predicted-the-future-we-live-in

Question: According to Andy Beckett, accelerationism addresses the “resetting of our minds and bodies by ever-faster music and films” (2017). With reference to specific media and/or music, what are the implications of accelerationism for the experience of everyday life?

6. Expanded cinema challenges traditional cinema. Discuss with reference to relevant theory and specific examples from the lecture and other sources if necessary (including your own practice where appropriate).

7. Failure is not the opposite of success, but the opposite of perfection. How can art embrace this failure? Discuss with reference to relevant theory and specific examplesfrom the lecture and other sources if necessary (including your own practice where appropriate).

8. Psychogeography can change both you and society. Discuss with reference to relevant theory and specific examples from the lecture and other sources if necessary (including your own practice where appropriate).

9. “The essence of technology is nothing technological.” Discuss with reference to relevant theory and specific examples from the lecture and other sources if necessary (including your own practice where appropriate).

10. The challenge is how to present sound only work in the context of moving image. How do you experience audio as a sound only movie? Discuss with reference to relevant theory and specific examples from the lecture and other sources if necessary (including your own practice where appropriate).

Rushton argues that “one should not concentrate on cinema’s capacities for representing reality, one should begin from the position that films are, in one way or another, part of reality”. (2013: 43-44) Using specific examples, examine the idea that films and/or other media are “part of reality".

Rushton claims that ‘digital cinema, so the argument goes, is a completely different beast from the cinema of celluloid, especially as films can now be made without any reference to ‘reality’ at all’ (Rushton, 2013) when talking about Bazin’s beliefs on cinema and reality. Arguing that Bazin is often misinterpreted by other theorists in ‘The Reality of Film’, Rushton takes the stance that there is more nuance to Bazin’s words; that film is inherently routed in reality despite some scholars arguing for cinema’s inherent artificiality. Rushton argues that film is not a copy or representation of reality; it is reality, introducing Bazin whose ideas include film as creating its own reality. This can be interpreted as film being routed in reality, but, more so, that film is its own reality where audiences can experience a life together. In some cases, we may experience the same feelings as the others in the cinema but it can also be argued that film does not create its own reality and, rather, that film is a representation of the creator’s reality, taking the audience into the mind of the director.

While it is true in some sense that film is, in a way, routed in reality, there is also a more modern stance to be taken on the subject regarding artificial intelligence and its role in the current media landscape. AI, inherently in the name, suggests a false approach to the realm of film and media as a whole and is more widely being used by executives and companies to improve their workload and time management, whilst also taking jobs from creatives in the space. Artificial intelligence is both seen as a blessing and a curse in the creative space amongst critics and artists alike, allowing for mass production as well as mass unemployment. This essay will discuss the issues surrounding AI as a medium and its use in the arts, in relation to the reality of film. Is the modern use of AI a detriment to the fundamentals of Rushton’s ideas? Is AI fundamentally inhuman and, therefore, incapable of creating media routed in reality or, as a direct product of human intelligence and creativity, the ultimatum on human reality? Is AI a simulated thought, a copy rather than its own reality?

The nature of ‘film’ as we know it is constantly changing. The first film ever made is believed to be ‘Louis Le Prince’s Roundhay Garden Scene’, recorded in Leeds in England in 1888, at approximately 2 seconds long and shows some of Louis Le Prince’s family members walking around a garden. The movie was taken on Eastman Kodak paper-based photographic film and replayed using a projector which projected the images in sequence onto a clear wall. While this was the first film ever made, it is hard to believe just how far technology has come since the late 1800s. After this, many films were made on a roll of film, hence the reason why we call movies today films, despite no longer being taken on a film roll. This practice quickly lost its prominence in the 1990s when digital cinematography became a cheaper and more effective way of producing a video. The first film entirely shot on a digital camera, a prototype Sony DVW-700WS and a prosumer Sony DCE-VX1000, was ‘Windhorse’, an independent film shot in Tibet in 1996. ‘Star Wars Episode II: Attack of the Clones’ (2002) also paved the way for Hollywood to take on the digital camera rather than the film camera. As a more efficient way of storing data, digital technologies overtook analogue methods rapidly and we now live in a society where anyone can take out their phone and create a movie. In ‘Speed and Politics’, Paul Virilio puts this ‘accelerated culture’ into words, describing the increased speed of technology production in relation to capitalism; ‘history progresses at the speed of its weapon systems’ (Virilio, 2006). Because of the need for more money and power, outdated, expensive technologies are left behind for newer, cheaper alternatives. This has then led to society’s disconnect to analogue technologies such as the film camera, and, although it was a few decades ago that movies were captured on a tangible piece of media, young people today recognise this as a distant past and see digital cameras as being the norm. In this sense, our perception of what a film is has changed over the years: it is no longer a tangible object one can hold in their hand, but a series on zeros and ones held on a computer, only accessed via digital technologies. While a film may once have had some grounding in reality as a physical piece of media, it is now less so as it can no longer be held in one’s hand. The disconnect between consumer and product is now greater than it was before, suggesting there is less reality in the content. Despite this, however, the videographer is still ‘selecting that sight from an infinity of possible sights’ (Berger, 1972), and therefore has its meaning routed in the reality of humanity. What is being filmed is, in essence, still tangible and physical: the actors are real, often the set is real and, most importantly, the story has been created through the experiences of a human being, allowing it to have some grounds in reality. However, as technology has progressed, and our idea of what a film is has changed, artificial intelligence is moving into the scene, once again changing our perspective on what art is.

When talking about AI, it is important to note its rapid change in society as a whole. Mobile phones, large corporations and even the general public are using artificial intelligence more and more as part of everyday life. As many people are becoming computer-literate and using technologies available to us, the vast use of AI is inevitable. This inevitability will likely one day make its way to cinema, once again changing the way we view cinema as a form of reality. Russel J. A. Kilbourn explains that ‘a photograph, therefore, is in this sense like a finger- or footprint, left behind at the scene of a crime, indices or traces heralding the actual presence of someone who was there and is now passed on’ (Kilbourn, 2013). This can also be taken in the context of cinema, since a film is taken through the perspective of a human being, therefore having some relation to reality. Many audiences notice this and often film is seen as an expression of one’s thoughts and experiences, telling a story, while it may be fantastical and seemingly unreal, that has some connection to its author. For example, a British comedy, no matter how strange and unrealistic it may seem, may appear more negative than a comedy written by an American writer: as Stephen Fry once said, ‘the American comic hero is a wise-cracker who is above his material and who is above the idiots around him’ whereas the British comic is someone ‘whose sense of dignity is compromised by the world letting him down’ (anc6368, 2012). The cultural factors related to the writers of these sketches are clearly having an impact on the material produced, or more widely; ‘the contradictory histories of subjectivity within materialist aesthetic must occur without reactionary existential, expressionist and neo-expressionist, romantic and neo-romantic, politic’ (Gidal, 1989) to be deemed no longer a product of humanity. Artificial intelligence, however, seems to be blurring the lines between reality and computer generated. A viral video of Will Smith eating spaghetti made the rounds on social media a year ago in April 2023. While this was clearly made with the use of AI, it cannot be denied the sheer intelligence of these AI models, especially given the short time frame that this technology has existed. Yet, even in the last year, this technology has improved drastically, producing almost picture-perfect images of Will Smith eating spaghetti. Platforms, such as Open AI’s Sora, have come into play in recent months and it is astonishing to see the difference between one year to the next, making it hard to distinguish between what is real and what is AI generated. This will, indefinitely, be used in Hollywood, as Lev Manovich states, ‘cinema [has become] a slave to the computer’ (Manovich, 2001). As we move closer and closer to the normal use of AI, will we become more numb to it and see it as a genuine form of cinema? Is AI art becoming a part of cinematic reality and will we be able to distinguish between what is real and what is AI generated?

![]()

![]()

![]()

2. Please do the following reading and answer the question below:

Rushton, R. (2013) ‘Realism, Reality and Authenticity’, in The Reality of Film: Theories of Filmic Reality, Manchester: Manchester University Press, pp. 42-78.Source:https://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/westminster/reader.action?docID=1069669

Question: Rushton argues that “one should not concentrate on cinema’s capacities for representing reality, one should begin from the position that films are, in one way or another, part of reality”. (2013: 43-44) Using specific examples, examine the idea that films and/or other media are “part of reality".

3. Please do the following reading and answer the question below:

Tsitsos, W. (2018) ‘Race, Class, and Place in the Origins of Techno and Rap Music’, in Popular Music and Society, Vol. 41(3), 270-292. Source: https://www-tandfonline-com.uow.idm.oclc.org/doi/pdf/10.1080/03007766.2018.1519098?needAccess=true

Question: According to Tsitsos, “music constitutes a ritualistic attempt to symbolically purge that which does not belong” (2018: 272). Discuss the representation of race and/or class in relation to multiple examples of contemporary popular music and/or media.

4. Please do the following reading and answer the question below:

Bartmanski, D. and Woodward, I. (2015) Vinyl: the analogue medium in the age of digital reproduction', in The Journal of Consumer Culture, Vol. 15(1), pp. 3-27.Source:https://journals-sagepub-com.uow.idm.oclc.org/doi/epub/10.1177/1469540513488403

Question: For Bartmanski and Woodward, the continued relevance of the vinyl record as an “auratic cultural icon ... sums up an important aspect of late modernity – the searchfor authenticity and meaning through the heavily mediated, digitalised andcommodified world” (2015: 19). With reference to the continued relevance of one analogue format, platform or medium, discuss the meaning of authenticity in the age of digital reproduction.

5. Please do the following reading and answer the question below:

Beckett, A. (2017) ‘Accelerationism: how a fringe philosophy predicted the future we live in’, The Guardian, Thursday 11 May 2017.3 Source: https://www.theguardian.com/world/2017/may/11/accelerationism-how-a-fringe-philosophy-predicted-the-future-we-live-in

Question: According to Andy Beckett, accelerationism addresses the “resetting of our minds and bodies by ever-faster music and films” (2017). With reference to specific media and/or music, what are the implications of accelerationism for the experience of everyday life?

6. Expanded cinema challenges traditional cinema. Discuss with reference to relevant theory and specific examples from the lecture and other sources if necessary (including your own practice where appropriate).

7. Failure is not the opposite of success, but the opposite of perfection. How can art embrace this failure? Discuss with reference to relevant theory and specific examplesfrom the lecture and other sources if necessary (including your own practice where appropriate).

8. Psychogeography can change both you and society. Discuss with reference to relevant theory and specific examples from the lecture and other sources if necessary (including your own practice where appropriate).

9. “The essence of technology is nothing technological.” Discuss with reference to relevant theory and specific examples from the lecture and other sources if necessary (including your own practice where appropriate).

10. The challenge is how to present sound only work in the context of moving image. How do you experience audio as a sound only movie? Discuss with reference to relevant theory and specific examples from the lecture and other sources if necessary (including your own practice where appropriate).

Rushton argues that “one should not concentrate on cinema’s capacities for representing reality, one should begin from the position that films are, in one way or another, part of reality”. (2013: 43-44) Using specific examples, examine the idea that films and/or other media are “part of reality".

Rushton claims that ‘digital cinema, so the argument goes, is a completely different beast from the cinema of celluloid, especially as films can now be made without any reference to ‘reality’ at all’ (Rushton, 2013) when talking about Bazin’s beliefs on cinema and reality. Arguing that Bazin is often misinterpreted by other theorists in ‘The Reality of Film’, Rushton takes the stance that there is more nuance to Bazin’s words; that film is inherently routed in reality despite some scholars arguing for cinema’s inherent artificiality. Rushton argues that film is not a copy or representation of reality; it is reality, introducing Bazin whose ideas include film as creating its own reality. This can be interpreted as film being routed in reality, but, more so, that film is its own reality where audiences can experience a life together. In some cases, we may experience the same feelings as the others in the cinema but it can also be argued that film does not create its own reality and, rather, that film is a representation of the creator’s reality, taking the audience into the mind of the director.

While it is true in some sense that film is, in a way, routed in reality, there is also a more modern stance to be taken on the subject regarding artificial intelligence and its role in the current media landscape. AI, inherently in the name, suggests a false approach to the realm of film and media as a whole and is more widely being used by executives and companies to improve their workload and time management, whilst also taking jobs from creatives in the space. Artificial intelligence is both seen as a blessing and a curse in the creative space amongst critics and artists alike, allowing for mass production as well as mass unemployment. This essay will discuss the issues surrounding AI as a medium and its use in the arts, in relation to the reality of film. Is the modern use of AI a detriment to the fundamentals of Rushton’s ideas? Is AI fundamentally inhuman and, therefore, incapable of creating media routed in reality or, as a direct product of human intelligence and creativity, the ultimatum on human reality? Is AI a simulated thought, a copy rather than its own reality?

The nature of ‘film’ as we know it is constantly changing. The first film ever made is believed to be ‘Louis Le Prince’s Roundhay Garden Scene’, recorded in Leeds in England in 1888, at approximately 2 seconds long and shows some of Louis Le Prince’s family members walking around a garden. The movie was taken on Eastman Kodak paper-based photographic film and replayed using a projector which projected the images in sequence onto a clear wall. While this was the first film ever made, it is hard to believe just how far technology has come since the late 1800s. After this, many films were made on a roll of film, hence the reason why we call movies today films, despite no longer being taken on a film roll. This practice quickly lost its prominence in the 1990s when digital cinematography became a cheaper and more effective way of producing a video. The first film entirely shot on a digital camera, a prototype Sony DVW-700WS and a prosumer Sony DCE-VX1000, was ‘Windhorse’, an independent film shot in Tibet in 1996. ‘Star Wars Episode II: Attack of the Clones’ (2002) also paved the way for Hollywood to take on the digital camera rather than the film camera. As a more efficient way of storing data, digital technologies overtook analogue methods rapidly and we now live in a society where anyone can take out their phone and create a movie. In ‘Speed and Politics’, Paul Virilio puts this ‘accelerated culture’ into words, describing the increased speed of technology production in relation to capitalism; ‘history progresses at the speed of its weapon systems’ (Virilio, 2006). Because of the need for more money and power, outdated, expensive technologies are left behind for newer, cheaper alternatives. This has then led to society’s disconnect to analogue technologies such as the film camera, and, although it was a few decades ago that movies were captured on a tangible piece of media, young people today recognise this as a distant past and see digital cameras as being the norm. In this sense, our perception of what a film is has changed over the years: it is no longer a tangible object one can hold in their hand, but a series on zeros and ones held on a computer, only accessed via digital technologies. While a film may once have had some grounding in reality as a physical piece of media, it is now less so as it can no longer be held in one’s hand. The disconnect between consumer and product is now greater than it was before, suggesting there is less reality in the content. Despite this, however, the videographer is still ‘selecting that sight from an infinity of possible sights’ (Berger, 1972), and therefore has its meaning routed in the reality of humanity. What is being filmed is, in essence, still tangible and physical: the actors are real, often the set is real and, most importantly, the story has been created through the experiences of a human being, allowing it to have some grounds in reality. However, as technology has progressed, and our idea of what a film is has changed, artificial intelligence is moving into the scene, once again changing our perspective on what art is.

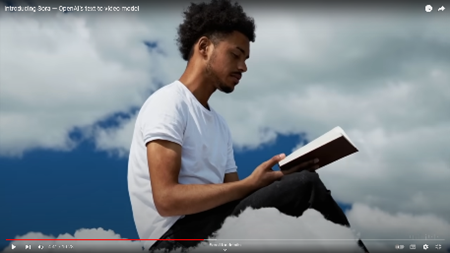

When talking about AI, it is important to note its rapid change in society as a whole. Mobile phones, large corporations and even the general public are using artificial intelligence more and more as part of everyday life. As many people are becoming computer-literate and using technologies available to us, the vast use of AI is inevitable. This inevitability will likely one day make its way to cinema, once again changing the way we view cinema as a form of reality. Russel J. A. Kilbourn explains that ‘a photograph, therefore, is in this sense like a finger- or footprint, left behind at the scene of a crime, indices or traces heralding the actual presence of someone who was there and is now passed on’ (Kilbourn, 2013). This can also be taken in the context of cinema, since a film is taken through the perspective of a human being, therefore having some relation to reality. Many audiences notice this and often film is seen as an expression of one’s thoughts and experiences, telling a story, while it may be fantastical and seemingly unreal, that has some connection to its author. For example, a British comedy, no matter how strange and unrealistic it may seem, may appear more negative than a comedy written by an American writer: as Stephen Fry once said, ‘the American comic hero is a wise-cracker who is above his material and who is above the idiots around him’ whereas the British comic is someone ‘whose sense of dignity is compromised by the world letting him down’ (anc6368, 2012). The cultural factors related to the writers of these sketches are clearly having an impact on the material produced, or more widely; ‘the contradictory histories of subjectivity within materialist aesthetic must occur without reactionary existential, expressionist and neo-expressionist, romantic and neo-romantic, politic’ (Gidal, 1989) to be deemed no longer a product of humanity. Artificial intelligence, however, seems to be blurring the lines between reality and computer generated. A viral video of Will Smith eating spaghetti made the rounds on social media a year ago in April 2023. While this was clearly made with the use of AI, it cannot be denied the sheer intelligence of these AI models, especially given the short time frame that this technology has existed. Yet, even in the last year, this technology has improved drastically, producing almost picture-perfect images of Will Smith eating spaghetti. Platforms, such as Open AI’s Sora, have come into play in recent months and it is astonishing to see the difference between one year to the next, making it hard to distinguish between what is real and what is AI generated. This will, indefinitely, be used in Hollywood, as Lev Manovich states, ‘cinema [has become] a slave to the computer’ (Manovich, 2001). As we move closer and closer to the normal use of AI, will we become more numb to it and see it as a genuine form of cinema? Is AI art becoming a part of cinematic reality and will we be able to distinguish between what is real and what is AI generated?

Taken

from Will Smith eating spaghetti AI video, 2023

Watch the whole video here: https://youtu.be/vbWe5k4fFWE?si=4KTFJpVnBSR2_dYS

Watch the whole video here: https://youtu.be/vbWe5k4fFWE?si=4KTFJpVnBSR2_dYS

Taken

from Will Smith eating spaghetti AI video, 2024

Watch the whole video here: https://youtu.be/vbWe5k4fFWE?si=4KTFJpVnBSR2_dYS

Watch the whole video here: https://youtu.be/vbWe5k4fFWE?si=4KTFJpVnBSR2_dYS

Taken

from OpenAI’s ‘Introducing Sora’ video, 2024

Watch the whole video here: https://youtu.be/HK6y8DAPN_0?si=H5ew8--9XLbqZxLS

Watch the whole video here: https://youtu.be/HK6y8DAPN_0?si=H5ew8--9XLbqZxLS

This shift towards new technologies

is nothing new and is a direct result of capitalism. Elster explains that a

‘purely “commercial” or capitalist government would be too myopic or greedy’ (Elster,

1986) when talking about Marxist ideas suggesting that capitalism is the start

of all industry and, in turn, greed. Many workers have lost their jobs due to

the nature of machines taking over day-to-day jobs, making the rich richer and

the poor homeless. This could then be used as a basis for how AI is being used

in the world today: as a means to take creators’ jobs in the pursuit of profit.

Shawn Michelle Smith and Sharon Sliwinski quote Brecht in ‘Photography and the

Optical Unconscious’ with the idea that ‘ “photography, in the hands of the

bourgeoisie, has become a terrible weapon against truth” ‘ (Smith, Sliwinski,

2017) suggesting that lies are being told by the media in order to incur

profit; thus gaining from the capitalist regime. In the age of artificial

intelligence, this can be further added upon since the very nature of AI is a

lie, no longer an image of reality. On the contrary, however, some might argue

that AI does hold some truth to it as it is an algorithm designed by humans. It

learns about images and knowledge taken from our own research and combines it

all to reach a conclusion. With the idea of film production through the use of

AI, the program takes in lots of information from other sources, such as videos

and films taken from real people, and uses the knowledge and algorithms it has

learnt to create something new, which is then informed by the prompter’s

prompt. AI videos may not have much direct human creativity but it does use the

creativity of humanity to come to its conclusion. But is this true creativity

and, therefore, have relation to reality? Some may argue that yes, it is still

grounded in reality but others would starkly disagree. AI models, such as Sora,

are taking the works from others and taking away the human experience from each

to create a completely computerised work. Artists (who originally created this

work) are being removed from jobs because “AI can do it better” and more

efficiently. The cheap nature of AI art and its wide accessibility makes it desirable

to small companies who can’t afford to hire artists but it may also be seen as

a way for large corporations to cut costs themselves. ‘To earn money, they are

willing to nevertheless enable us to produce a (damaging) film’ (Brecht,

Silberman, 2001) which has little to no grounds in reality. Rather than an open

source as it has been previously, AI is becoming more and more

American-centred, owned by a few tech giants meaning that the data which AI is

using is potentially biased towards these companies and the Western world as a

whole. This is a direct result of the West’s capitalist regime which has led to

this wide spread use resulting in media which isn’t always suited for screen

and often misrepresents the cultures and personal experiences of directors and

creators alike. “The complex web of human interactions that thrived on the

internet’s initial technological diversity is now corralled into globe-spanning

data-extraction engines making huge fortunes for a tiny few.” (Farrell, Berjon,

2024) Unfortunately, the idea that we can discern the difference between

what is real and what is AI is rapidly changing. It is becoming harder and

harder to tell when something is not real as shown by the Will Smith video and

it could get to the point where cinema is all AI generated and this becomes our

new reality.

While this may be a bleak way to end this discussion, it is important to recognise our current reality and its trajectory in order to speak up against those who create it. While film and other media outlets are a crucial part of society at large and AI is becoming a subject of discussion in that respect, the reality of film has changed since its inception and it is still changing. Even ‘the reader is constantly ready to become a writer’ (Benjamin, 1936) and many people own phones and can access these services themselves. Creators will use, not just AI, but filters and effects to improve their image online and present that as reality. The sense that “reality is what you make it to be” seems to be a driving force in today’s world and AI is just one piece of that which we are not yet fully comfortable with. ‘Except in the case of a few people who are, as we say, “possessed” by art, it doesn’t seem to venture to encroach on the realm of reality’ (Freud, 2003) and many people can recognise the difference between falsehood and truth. So, while this line is indeed blurring, the “uncanny valley” effect that AI is producing right now has caused many artists concern and there is a current debate going on surrounding its use in media, especially when paired with the artist lay-offs. While I disagree with Rushton that film creates its own reality, it can be said that AI creates its own reality without being centred in the true reality whatsoever, but that that may be an unfortunate trajectory we are currently facing. In conclusion, cinema does hold some reality as all man-made art is derived from the experiences and views of the artist and audiences will often recognise this yet, when it comes to the use of AI, there is a wider discussion that needs to be had about its impact on society and the reality of film.

Bibliography

anc6368 (2012) Stephen Fry on American vs British Comedy [video], Available at: https://youtu.be/8k2AbqTBxao?si=6ic-3sQxpAIiiKqU (Accessed: 30/04/2024)

Benjamin, W (1936) The Work of Art in the age of Mechanical Reproduction [book], London: Penguin Books Ltd

Berger, J (1972) Ways of Seeing [book], London: Penguin Books Ltd

Brecht, B. and Silberman, M. (2001) On Film and Radio [book], London: Methuen.

Elster, J. (1986) An introduction to Karl Marx [book], Cambridge University Press.

Ferrell, M and Berjon, R (2024) We Need To Rewild The Internet [article], Available at: https://www.noemamag.com/we-need-to-rewild-the-internet/ (Accessed: 06/05/2024)

Freud, S. (2003) An Outline of Psychoanalysis [book], London: Penguin Books.

Gidal, P. (1989) Materialist Film [book], London: Routledge.

Kilbourn, R.A.J. (2013) Cinema, Memory, Modernity: The representation of memory from the art film to Transnational Cinema [book] London: Routledge.

Manovich, L (2001) The Language of New Media [book], Cambridge: Massachusetts Institute of Technology

Rushton, R. (2013) ‘Realism, Reality and Authenticity’, in The Reality of Film: Theories of Filmic Reality [online], Manchester: Manchester University Press, pp. 42-78. Available at: https://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/westminster/reader.action?docID=1069669 (Accessed: 26/04/2024)

Smith, S.M. and Sliwinski, S. (2017) Photography and the Optical Unconscious[book], Durham: Duke University Press.

Virilio, P. (2006) Speed and Politics [book] Los Angeles, CA: Semiotext(e).

While this may be a bleak way to end this discussion, it is important to recognise our current reality and its trajectory in order to speak up against those who create it. While film and other media outlets are a crucial part of society at large and AI is becoming a subject of discussion in that respect, the reality of film has changed since its inception and it is still changing. Even ‘the reader is constantly ready to become a writer’ (Benjamin, 1936) and many people own phones and can access these services themselves. Creators will use, not just AI, but filters and effects to improve their image online and present that as reality. The sense that “reality is what you make it to be” seems to be a driving force in today’s world and AI is just one piece of that which we are not yet fully comfortable with. ‘Except in the case of a few people who are, as we say, “possessed” by art, it doesn’t seem to venture to encroach on the realm of reality’ (Freud, 2003) and many people can recognise the difference between falsehood and truth. So, while this line is indeed blurring, the “uncanny valley” effect that AI is producing right now has caused many artists concern and there is a current debate going on surrounding its use in media, especially when paired with the artist lay-offs. While I disagree with Rushton that film creates its own reality, it can be said that AI creates its own reality without being centred in the true reality whatsoever, but that that may be an unfortunate trajectory we are currently facing. In conclusion, cinema does hold some reality as all man-made art is derived from the experiences and views of the artist and audiences will often recognise this yet, when it comes to the use of AI, there is a wider discussion that needs to be had about its impact on society and the reality of film.

Bibliography

anc6368 (2012) Stephen Fry on American vs British Comedy [video], Available at: https://youtu.be/8k2AbqTBxao?si=6ic-3sQxpAIiiKqU (Accessed: 30/04/2024)

Benjamin, W (1936) The Work of Art in the age of Mechanical Reproduction [book], London: Penguin Books Ltd

Berger, J (1972) Ways of Seeing [book], London: Penguin Books Ltd

Brecht, B. and Silberman, M. (2001) On Film and Radio [book], London: Methuen.

Elster, J. (1986) An introduction to Karl Marx [book], Cambridge University Press.

Ferrell, M and Berjon, R (2024) We Need To Rewild The Internet [article], Available at: https://www.noemamag.com/we-need-to-rewild-the-internet/ (Accessed: 06/05/2024)

Freud, S. (2003) An Outline of Psychoanalysis [book], London: Penguin Books.

Gidal, P. (1989) Materialist Film [book], London: Routledge.

Kilbourn, R.A.J. (2013) Cinema, Memory, Modernity: The representation of memory from the art film to Transnational Cinema [book] London: Routledge.

Manovich, L (2001) The Language of New Media [book], Cambridge: Massachusetts Institute of Technology

Rushton, R. (2013) ‘Realism, Reality and Authenticity’, in The Reality of Film: Theories of Filmic Reality [online], Manchester: Manchester University Press, pp. 42-78. Available at: https://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/westminster/reader.action?docID=1069669 (Accessed: 26/04/2024)

Smith, S.M. and Sliwinski, S. (2017) Photography and the Optical Unconscious[book], Durham: Duke University Press.

Virilio, P. (2006) Speed and Politics [book] Los Angeles, CA: Semiotext(e).